Uncategorized

East Africa’s crackdown on dissent deepens as citizens demand democracy

By Burnett Munthali

In recent months, Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania have intensified efforts to suppress public protests, raising alarm over the shrinking space for democratic expression in East Africa.

In Kenya, the commemoration of Saba Saba—an annual pro-democracy event—turned into a nationwide outcry as thousands, mostly youth, took to the streets demanding economic justice and accountability.

The government responded with brute force, deploying tear gas, water cannons, and live bullets to disperse the demonstrators.

The outcome was tragic: at least 31 people were killed, over 500 arrested, and hundreds more injured during the clashes.

Among the rallying cries of the protestors was the call for justice over the death of blogger Albert Ojwang, who died under suspicious circumstances while in police custody.

Cities such as Nairobi, Eldoret, and Nyeri were brought to a standstill as malls, schools, and major roads were closed amid a government-imposed security clampdown.

Despite mounting tensions, the government maintained a hardline stance, declaring zero tolerance for what it termed “unlawful assemblies.”

International organizations, including the United Nations and human rights watchdogs, strongly condemned the violent crackdown, urging the Kenyan government to respect fundamental freedoms.

President William Ruto, now under immense pressure, faces a generational revolt spearheaded by tech-savvy, socially active Generation Z, whose online activism has driven hashtags like #RutoMustGo to viral status.

Meanwhile, in Uganda, President Yoweri Museveni—who has ruled since 1986—continues to wield authoritarian control, bolstered by legal restrictions, military intimidation, and a deeply entrenched patronage system.

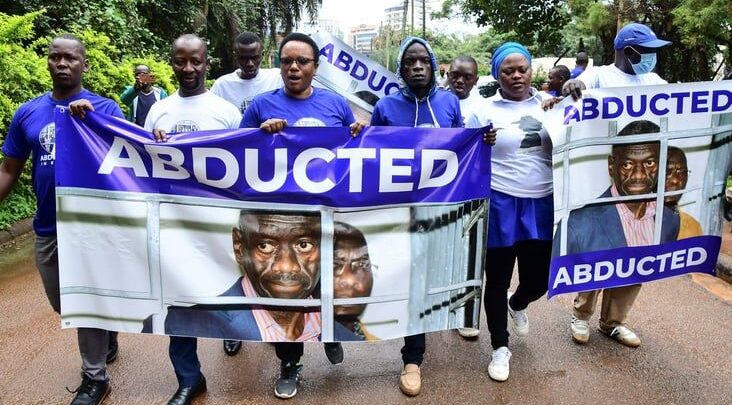

Protests and dissent are routinely met with swift and harsh repression, and opposition voices are frequently silenced through arrests, surveillance, and intimidation.

In Tanzania, hopes that President Samia Suluhu Hassan would usher in political reform have faded.

Instead, her administration has moved to ban the main opposition party Chadema, arrest its leaders including Tundu Lissu, and detain foreign activists who voiced support for democracy.

Human rights groups have reported a surge in forced disappearances, abductions, and torture, painting a grim picture of democratic backsliding in what was once seen as a stable nation.

In all three countries, security forces are increasingly militarized, justifying violent crackdowns as necessary for maintaining law and order.

Governments have also turned to legislative tools, issuing bans on public gatherings and media coverage, and enacting repressive laws to stifle civil society.

Despite these measures, East Africa’s youth are mobilizing in new and creative ways, using social media to document abuses, organize protests, and demand systemic change.

International actors, including the European Union and the United States, have expressed concern and called on these governments to uphold democratic principles and human rights.

Still, the region’s political elites appear determined to maintain their grip on power, even at the cost of suppressing popular will.

As elections loom across East Africa, the struggle between state control and grassroots democracy is intensifying.

Whether these nations will heed the call for reform or entrench deeper authoritarianism remains a critical question for the region’s future.